Back To School, With Tea

Gongliuzi Tea Institute 公刘子 in Hangzhou

I have been blogging about my recent month-long journey to Hangzhou, Huangshan and Anhui province in eastern China. My main objective on this trip was to obtain the demanding Tea Artisan and Tea Assessor qualifications of China’s Labour Ministry. After years of private study and research, the thought of taking public examinations felt exposing and daunting, but I am glad I went through with it, because I can now proudly call myself an officially certified Tea Artisan and Tea Assessor.

My cosy little classroom at the 公刘子 Gongliuzi Tea Institute in Hangzhou was furnished with antique desks, a blackboard with coloured chalk, and, naturally, lashings of tea. My teachers were a fine, inspiring group of aficionados and experts:

Professor Tang Yi talking about classification of tea

Professor Tang Yi talking about classification of teaProfessor Zhou Wentang 周文棠, Miss Hu Xuli 胡旭丽, Miss Zhang Xiaolei 张晓蕾, Miss Cheng Xiaohong 程小红 and guest lecturers Professor Yu Fulian 虞富莲 (Tea Research Faculty of the China Agriculture Institute) and Professor Tang Yi 汤一 (Zhejiang University – Tea Faculty).

Subjects covered included the history of tea, the literature and poetry of tea, the art of tea performance and the identification and grading of tea varieties. We were given ancient tea texts to read in the classical Chinese, but also, excitingly for me, we read selected passages from the the world’s first tea book, 茶经 Chajing or the ‘Tea Classic’ written in AD 785 by Lu Yu (733-804).

Teacher Hu demonstrating moistening Dragon Well Green Tea leaves – one of the many gestures of the Green Tea Ceremony

Lu Yu writes extensively about the cultivation, harvesting, processing, storage, brewing and drinking of tea as well as the history of tea culture. The Chajing is regarded as an extremely important historical text not just on tea but on ancient Chinese culture generally.

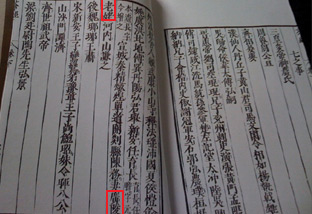

With just four Chinese characters “广陵老姥”, Lu Yu writes that during the reign of Emperor Yuan (AD 276-323) of the Jin dynasty (AD 265-420), there was an elderly woman who would carry a huge pot of 雨花 Yuhua green tea to sell along the street market. Her business was brisk and she donated all her proceeds to the poor. Over time, her customers noticed that her pot was never empty, even though she sold tea the whole day. The real reason was that she kept adding hot water all day, as it is perfectly possible to re-brew good quality teas several times over; but the townspeople thought that she must be practising witchcraft so they locked her and her pot up in a prison cell.

With just four chinese characters (outlined in red), Lu Yu writes about the strange old woman whose tea pot was never empty in the Chajing or ‘Tea Classic’.

With just four chinese characters (outlined in red), Lu Yu writes about the strange old woman whose tea pot was never empty in the Chajing or ‘Tea Classic’.By nightfall, she is said to have flown out through the tiny prison window, taking her pot with her. The story is probably true up until the bit where she flew away! Interestingly, it conveys the impression that brewing and then selling tea as a drink was highly unusual at this time; I could very well imagine that the story is a semi-mythical version of the actual origination of the traditional Chinese tea house, which I think is a fascinating concept.

A major section of my Tea Artisan training concerned the physical processes of making and presenting tea: constant going over and over the correct implements and the right ritual movements and postures appropriate for each tea type; when and how to bow, which hands and fingers to organize into what precise gestures, and so on. This is all prescribed for the sake both of smooth efficiency and to be a visual delight, all part of the tea drinker’s experience.

Learning how to sit gracefully with teacher Hu

By the end, I had progressed to a point where I can use my body quite gracefully and with calmness and a sense of flow – but this was definitely the toughest part of the course. The girls had it even worse – they have a whole different set of movements and gestures of their own, involving physically demanding curtseying, flowing and gesturing. We all experienced plenty of aches and pains, in the name of the art of tea (‘Cha Tao’)!

Professor Zhou Wentang talking about ChaJing, the Classics of Tea

The Tea Assessor course, by contrast, focused on understanding the commercial grading of tea and on the complex chemical reactions that occur when tea is brewed. I had to learn to memorize long lists of tastes and colours associated with particular types of tea, an odd mixture of the subjective and the objective. For example, such and such tea might be expected to have the aroma of freshly steamed, tender sweetcorn with a glutinous texture, while another tea might be reminiscent of fried Chinese chestnuts. I have a pretty comprehensive knowledge of Chinese foods but some of these comparisons were hard to take on board, and as for the Chinese descriptions of colours, these can be very difficult to differentiate from one another.

The Tea Assessor exam came in two parts. In the practical section, I was asked to evaluate and rank three grades of Dragon Well within 20 minutes, using the standard tea assessing equipment. This year, the untimely rain at Qing Ming (the Clear Bright Festival or Tomb Sweeping Day around April 5) seriously affected the Dragon Well harvest, making it particularly difficult to tell the grades apart – very unlucky for me, though I did managed to rank the tea correctly!

Every day of this tea journey was filled with new knowledge, heartwarming stories and continued reminder that the study of tea is indeed a life long process. I met many tea friends and was touched by the unspoken code of friendliness, sincerity and generosity amongst tea artisans. And I’ve brought back home to the UK so many tea books I can’t wait to read them all and share more discoveries with you in my future blogs!

Warmly,

Pei

pei@teanamu.com

~~ sip a good brew, steal a slice of tranquility, glimpse a lingering fragrance, gladden the heart and refresh the mind ~~

I see myself,sit beside you,haha…

Though be 3 days classmate, I will never forget the wonderful experience there.

Hi Yivan,

Indeed, it is a wonderful experience for me too. I hope to go back to continue my tea study in a year or two.