Lu Yu: Classic of Tea Chapter 4 (Part III)

Tea saint Lu Yu’s Classic of Tea Chapter 4 in its original text. (To view the Chinese characters in this blog, you may need to enable character encoding of your web browser to either Unicode or Simplied Chinese.)

In this third and last part of Classic of Tea Chapter 4, I’ve been entertaining myself translating items 10 to 25 listed by Lu Yu. Let’s get started!

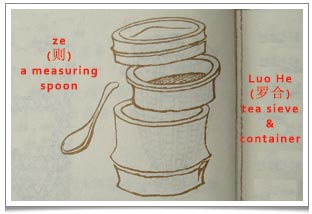

Tea was consumed in powder form in China in Lu Yu’s day, and the first item (Item 10) comprises a “luo” (罗) or sieve made from silk or muslin stretched across a big chunky bamboo section, placed over a “he” (合) which was a painted bamboo or cedar box to hold the finely sieved tea powder. It’s a bit like a modern cheese grater in structure! The “he” was 3 cun (寸 inch) tall with a 1 cun lid, a base of 2 cun and a 4 cun opening.

Item no. 11 is a “ze” (则), a measuring scoop made from a sea shell or clam shell, or else fashioned from copper, iron or bamboo. Lu Yu says that, according to one’s taste, 1 “sheng” (升, or litre) of boiling water requires about 1 square inch or 2g freshly ground tea powder. The reference to the square inch volume of tea echoes Chinese traditional medicine where a square (1 inch) spoon of 1 inch sides was used to measure out medicinal herbs.

Table of Contents

“Cha Jing” The Classic Treatise of Tea

by Lu Yu (760-780AD)

One: Origin 一之源:- This chapter expounds the mythological origins of tea in China. It also contains a horticultural description of the tea plant and its proper planting as well as some etymological speculation.

Two: Tools 二之具 (Part 1) & (Part 2):- This chapter describes 16 tools for picking, steaming, pressing, drying and storage of tea leaves and cake.

Three: Making 三之造:- This chapter details the recommended procedures for the production of tea cake.

Four: Utensils 四之器 (Part I), (Part II) & (Part III):- This chapter describes twenty five items used in the brewing and drinking of tea.

Five: Boiling 五之煮:- This chapter enumerates the guidelines for the proper preparation of tea.

Six: Drinking 六之飲:- This chapter describes the various properties of tea, the history of tea drinking and the various types of tea known in 8th century China.

Seven: History 七之事:- This chapter gives various anecdotes about the history of tea in Chinese records, from Shennong through the Tang dynasty.

Eight: Growing Regions 八之出:- This chapter ranks the eight tea producing regions in China.

Nine: Simplify 九之略:- This chapter lists those procedures that may be omitted and under what circumstances.

Ten: Pictorial 十之圖:- This chapter consists of four silk scrolls that provide an abbreviated version of the previous nine chapters.

“Shui fang”, the 12th item listed by Lu Yu, is simply a water container with a volume of 1 “dou” (斗) = 10 sheng or roughly 10 litres. It was made of “chou” (椆) wood, “huai” (槐, pagoda wood) or “qiu” (楸) or “zi” (梓) both forms of catalpa wood, and painted inside and out so that it couldn’t leak.

The 13th item is a “Lu Shui Nang” (漉水囊), a filter used when pouring boiled tea for drinking. The filter frame was usually made from untreated copper, which prevented the accumulation of dirt which might spoil the taste of the tea. Lu Yu says that some hermits used a bamboo or wooden filter but these were not durable and not portable. The filter itself was made from weaved bamboo lined with fine silk of a jade green colour. One could also add beautiful jewels to decorate it. Also, the filter had a little pouch of green oil cloth to hold it or that could be used to hold a small amount of water. Lu Yu specifies his lu shui nang had a diameter of 5 cun and a 1.5 cun handle.

The next item is a water scoop called a “piao” (瓢) made from a “hu lu” (葫芦, calabash gourd) split into half vertically or from wood. The piao is usually thin with a wide opening and a short handle.

Item number 15 is the “zhu jia” (竹夹), foot-long tongs made out of bamboo, walnut, willow or Chinese palmetto. The two ends of the zhu jia were wrapped in a silver pouch.

In my mind’s eye I’m struck how beautifully, with some of these pieces, ostentatious jewels and silver would have contrasted with plain bamboo and other woods.

The 16th item “cuo gui” (鹾簋) is a cylindrical food container, 4 cun tall with a diameter 1/9th of a cun. Such containers were usually of bamboo, but Lu Yu’s cuo gui was made from porcelain and used to store salt. Salt was added to tea to bring out its umami sweetness. I will write more about this in another blog post.

Item 17 is a “shou peng” (熟盂), a porcelain or clay container used to hold 2 sheng (i.e. litres) of “cooked” (i.e. hot) water.

Item 18 gets Lu Yu quite excited. It is a “wan” (碗) or bowl for drinking tea. Lu Yu says wan made in Yue Zhou (越州, Zhejiang province Shaoxing area) are top quality, while those made in Ding Zhou (鼎州, Xiaxi province Jingyang Sanyang area), Wu Zhou (婺州, Jiangxi county Jinghua area) and Yue Zhou (岳州, Hunan province Yueyang area) are second rate, and those from Shou Zhou (寿州) and Hong Zhou (洪州) are downright poor.

A “luo” or sieve made from silk or muslin stretched across a big chunky bamboo section, placed over a “he” which was a painted bamboo or cedar box to hold the finely sieved tea powder. It’s a bit like a modern cheese grater in structure. A “ze” is a measuring scoop.

Lu Yu disagrees with some who say porcelain wans made in Xing Zhou (邢州, Hebei province, Xingtai area) are even better than those made in Yue Zhou . He offers three reasons. Rather poetically, he says that if porcelain from Xing Zhou is like silver then Yue Zhou porcelain is like jade (i.e. much better). If Xing Zhou porcelain is like snow then Yue Zhuo porcelain is like ice. And if the pure whiteness of Xing Zhou’s porcelain can make the tea acquire a beautiful reddish hue, then Yue Zhou’s porcelain can give the tea liquor a even more beautiful jade green colour.

Lu Yu then quotes an ancient text where porcelain made in Yue Zhou is considered the best. In it Yue Zhou bowls are described as having a non-curving rim and a shallow base with a volume of not more than half a “sheng”. Lu Yu then says that porcelain from Yue Zhou has a slightly blueish hue which brings out the colour of tea which is reddish. Porcelain from Xing Zhou is white and will therefore make the tea liquor even more red. Shou Zhou’s porcelain has a yellowish hue and will make the tea look more purple while the brownish porcelain of Hong Zhou makes the tea liquor look black. Lu Yu says only a wan from Yue Zhou is suitable for drinking tea.

“Shui fang” is simply a wooden water container of roughly 10 litres.

I find this section of Chapter 4 of particular interest. First, the drinking of boiled, powdered tea from a bowl has been picked up and adopted by the Japanese in their tea ceremony. Secondly, the fact that tea liquor is described as reddish suggests to me the tea commonly drunk in Lu Yu’s time was slightly more oxidised, consistent with the equipment used to dry and roast tea mentioned in my translation of Chapter 3 of Chajing.

Thirdly, I ache for those poor people who made porcelain bowls in Xing Zhou, Shou Zhou and Hong Zhou, so severely criticised in this classic book – it must have blighted their industry for centuries!

Item 19 is a “ben” (畚), a basket woven from a particular grass (fragaria nilgerrensis Schlecht – a genus of flowering plants in the rose family) that can hold up to 10 wans. Instead of a “ben”, Lu Yu says some people used a square bamboo holder made from paper.

The 20th item is “zha” (扎) which is a calligraphy brush made from the bark of the “bing tong” (栟榈, Chinese palm). The handle is made either from a section of bamboo or from cornel wood.

Lu Yu’s 21st item is the “di fang” (涤方), essentially a waste water bowl made from qiu wood and made just like the shui fang but with a volume of 8 sheng.

Item 22 is a “zi fang” (滓方) which is made just like the di fang and has a volume of 5 sheng. This is used to hold any used tea debris.

The 23rd item is “jin” (巾), a rough cloth used for cleaning tea-making utensils.

No. 24 is a “ju lie” (具列), a tea table made from wood or bamboo or both. Based on Lu Yu’s description, the ju lie looked rather like a modern coffee table with shelving or drawers. Lu Yu’s ju lie was painted black and yellow and its dimensions were 3 chi long, 2 chi wide and 6 cun tall.

The last item in this chapter is the “du lan” (都蓝), which holds all the other tea equipment. It is woven from bamboo to form triangular holes made by criscrossing 2 long strips of bamboo horizontally with 1 vertical strip. Lu Yu likes the du lan because it is ingeniously and delicately wrought. Lu Yu’s du lan is 1 chi 5 cun tall and has a base of 1 chi by 2 chi 4 cun.

It has been great fun translating chapter 4 (Part I and Part II) as it is the longest of all the chapters listing all 25 items that Lu Yu used in his tea ceremony. Many of these items are still used in the Chinese gongfu cha tea ritual that I used to brew tea for my tea friends at the many tea events I host and also in the Japanese tea ceremony. Indeed, there are some items like the ju lie or the luo he that might be the inspiration behind the modern day cheese grater and coffee table!

“Lu shui nang” is a filter used when pouring boiled tea for drinking. |

“Cuo Gui” is a cylindrical food container made from porcelain and used to store salt. |

|

“ben” is a basket woven from grass that can hold up to 10 tea drinking bowls. |

“Ju lie” is a tea table made from wood or bamboo or both. |

|

Warmly, Pei ~~ Serene and fragrant TEA entices with promise of rapture in STORE ~~ |