Gaiwan – Empress Dowager’s favourite teacup

How to use a gaiwan Chinese teacup: To use a gaiwan, hold the saucer with the 4 fingers of your right hand and let your thumb rests on the edge of the ‘wan’ or teacup. Use your left hand to hold the ‘gai’ or lid, with which you brush away any tea leaves before bringing the outward-curving rim of the ‘wan’ (tea cup) to your lips. Of course, the sticking out of the left pinkie like Empress Dowager is completely optional!

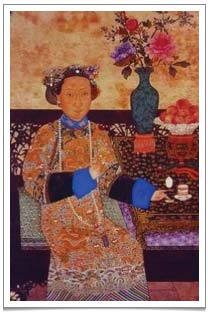

The TV ‘soaps’ I used to engross myself in as a young lad often seemed to feature a fearsome old lady holding a lidded Chinese teacup or ‘gaiwan’ (盖碗) in her extraordinary hands, drawing one’s eye to her amazingly long nails and her elegantly extended ‘pinkie’. This was the famous Empress Dowager who ruled China for much of the 19th century.

Gaiwans or Chinese teacups are a quintessential tea-drinking utensil in Chinese tea culture. They’re typically made from beautifully glazed ceramic or porcelain and consist of 3 components. Gaiwans are therefore sometimes called “san cai wan” (三才碗, three talent cup).

The topmost component is the “gai” (盖, lid) symbolising heaven. The middle component is the teacup itself or “wan” (碗, bowl used as a tea cup), symbolising the human sphere, and last but not least is the “tuo” (托, saucer) representing the earth or ground. The Chinese embody their concept of the universe through the gaiwan or Chinese teacup using it to show Man standing firmly on the Earth and holding up the Heaven.

The gaiwan as we know it was really formed during the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties. As early as the Tang dynasty (618-907), the Chinese had little teacups (with no handles) and only later, – the evidence suggests, in the Song dynasty (960-1279) – did they start to use saucers together with the teacups. During the Ming/Qing dynasties, a lid was added to form the complete three-part Chinese teacup or lidded teacup we have now.

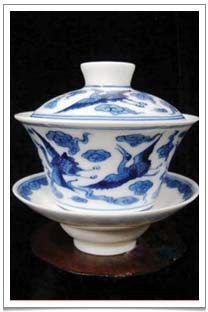

One of the four famous styles of porcelain gaiwans from Jing De Zheng (China) with blue and white glaze that we familiarly associate with Chinese teacups, vases and dishes.

The invention of the gaiwan has a folk tale attached to it. During the Tang dynasty, a certain Mr. Cui (崔), a government official who loved tea, had a very intelligent daughter. His daughter shared Mr. Cui’s passion for tea and consequently often burned her fingers rather than patiently waiting for her teacup (‘wan’) to cool down. Then she had the brainwave of holding a saucer in her hand to support the hot teacup. The trouble with this, she found, was that the teacup would tend to slip and slide around. Another danger! So another brainwave! She took a piece of soft wax, moulded it to fit the shape of the bottom of her teacup, and with it firmly attached the teacup to the saucer. The gaiwan was born. The best ideas are the simplest ones!

In Sichuan drinking tea from gaiwans or lidded teacups is a highly popular pastime. One of the favourite beverages in that region is Eight Treasures Tea (also Empress Dowager’s favourite tea). Putting eight types of dried flowers and fruits in a gaiwan to infuse is a rather delightful thing. The “Hui” (回族) people (a Chinese Muslim ethnic minority) have their own gaiwan tea ceremony. Traditionally, the Hui like to use the Chinese teacup or gaiwan as it beautifully reflects the cultured and graceful behaviour that Islam propounds.

The best quality porcelain gaiwans are made in “Jing De Zheng” (景德镇), the town of Jing De, in the north of Jiangxi province, eastern China. One of the four famous styles from Jing De Zheng is the blue and white glaze that we familiarly associate with Chinese teacups and lidded teacups in particular.

The advantages of the gaiwan are manifold. It’s smaller than a typical Chinese rice bowl and has a wider opening but a narrow bottom, thus allowing easy pouring of water. The gaiwan permits tea leaves to ‘dance’ and to give out their nutrition when water is added. The ‘wan’ or cup of the gaiwan has a thin rim that curves outwards making it easier to drink tea from. The ‘gai’ or lid is concave and smaller than the opening of the ‘wan’, which prevents it from slipping and most importantly keeps most the tea aroma in the ‘wan’. The ‘gai’ or lid can even be, and often is, used to gently sweep floating tea leaves away from the drinker’s lips. Or else the ‘gai’ is used for stirring the tea: the Chinese picturesquely call this “overturning the river and upsetting the sea” (翻江倒海, “fan jiang dao hai”).

A painting of the Empress Dowager in her casual costume drinking tea from her gaiwan teacup.

Some tea lovers who have bought gaiwans from me have asked, Why isn’t the lid of the teacup made so as to fit perfectly? The answer is simple: the gaiwan’s lid is deliberately made to not fit because one can then use it like a filter and also to allow steam to escape.

Gaiwans or lidded teacups are traditionally in use in both private homes and public tea houses. Many tea houses in China or Taiwan will serve you a gaiwan with your choice of tea leaves which you then are free to nurse all day long, chitchatting with your friends or playing chess or mahjong. There is an unspoken code whereby, if the gaiwan lid is resting on the gaiwan saucer, it signals that you require more water for the next infusion. Useful to know! In Sichuan tea houses, waiters will pour hot water from a kettle with an extremely long spout, in a sort of arc of hot water, allowing the tea leaves to tumble around in the gaiwan. The waiter will stop abruptly and as the remaining hot water reaches the gaiwan, the gaiwan is nearly filled to the rim. All without a single drop of water out of place, and nothing spilled!

Gaiwans are really easy to use. If I am drinking tea straight out of one, I hold the saucer with the 4 fingers of my right hand while my thumb rests on the edge of the ‘wan’ or teacup. I use my left hand to hold the ‘gai’ or lid, with which I brush away any tea leaves before bringing the outward-curving rim of the ‘wan’ to my lips. Of course, the sticking out of the left pinkie like Empress Dowager is completely optional! I love this way of drinking tea and frequently sit in our conservatory nursing my lidded cup and silently contemplating the red robin who comes to visit me from time to time.

I like the gaiwan because of its understated elegance. Don’t get me wrong: I can go a bit gaga over an exquisite Yixing purple clay tea pot but the simplicity of the gaiwan makes it an everyday tea utensil. I also like it because, in contrast to a seasoned Yixing purple clay pot, the quality and attributes of any tea have no place to hide in a gaiwan. One need not worry that the tea has been enhanced by the mere addition of hot water to an old pot (as can happen with a well seasoned Yixing pot). A poor quality tea will reveal itself.

Also it’s very easy to look at the brewed tea leaves in a Chinese lidded teacup. The tea liquor can be dispensed from the gaiwan a lot quicker than from a Yixing purple clay pot so one can control the brewing time a lot more easily.

If you would like to see or use a gaiwan, you can come to any one of our tea events or visit Bea’s of Bloomsbury who will be serving some teanamu teas in ritual style using the gaiwan.

P.S. I am accompanying my mother and brother on a Buddhist pilgrimage trip in the first three weeks of November. While it is primarily a spiritual trip for me, I am excited about possibility of understanding more about the tea culture of Northern India and in Nepal. I shall be back with my discoveries and pictures to share with you soon!

|

Warmly, Pei ~~ Serene and fragrant TEA entices with promise of rapture in STORE ~~ |