Enter Stage Right: Tea Garments and the Opera

One of the 2 designs of tea garment (‘cha yi’ 茶衣) employed in Chinese operas where the lapels meet in the middle of the torso (like a shirt).

Last July I enjoyed a fabulous evening of Beijing and Kunqu Opera presented by the London Jing Kun Opera Association together with AMC, the Asian Music Circuit.

Kunqu (昆曲) also known as Kunju (昆剧) is one of the oldest extant forms of Chinese opera. It was dominant from the 16th to 18th centuries. Beijing opera (or 京剧 Jīngjù ) developed in the mid 19th century and combines music and vocal performances with mime, dance and acrobatics.

Not only was it a personal treat and a delight for me to listen to classic opera pieces expertly sang, but the performers’ costumes were absolutely stunning. Many of these were later displayed in an exhibition called ‘Enter Stage Right’ put on by the AMC at their headquarters in west London. Along with each exhibited item came explanations of the fascinating symbolism contained in the costume designs.

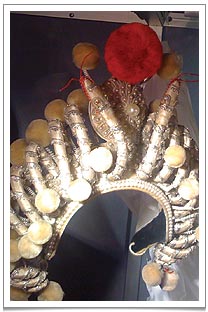

The intricate headdress showing little snakes with pom poms at the end from the ‘Legends of the White Snake’ (‘Bai She Chuan‘ 白蛇传).

The phoenix embroidered on to a dress, for example, tells the opera audience that the character is the consort of the Dragon i.e. she is the Emperor’s wife. Poenies and other flowers symbolise female beauty and fertility. Patterns of mountains, waves and clouds, sea sprays and the sun indicate a character’s importance. Especially for the illiterate masses, this was a really important part of how stories were conveyed.

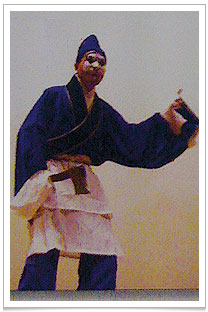

The character of the wine seller, in the story of Lin Chong, wearing the tea garment with the left lapel covers the right lapel (like a bathrobe).

I have always liked the ‘chou‘ (丑) or ‘fool’ characters in Chinese opera. They are hilarious clowns, equivalent to the punchinellos in Italian opera. Some are innkeepers, others play the role of ‘wen‘ (文) or ‘scholar’ , merchant, fisherman, carpenter or matchmaker. Some take roles that are physical, martial (‘wu‘ 武), even acrobatic – such as soldier or prison guard, for example. Relatively minor roles though they are, the accompanying orchestra reserves the use of drums, clapper, small gong and cymbals just for them.

One of these clown characters wears the ‘tea garment‘ – ‘cha yi‘ 茶衣 – a blue top and trousers with a white apron for wiping hands. There are two main designs, one where the left lapel covers the right lapel (like a bathrobe) and the other where the lapels meet in the middle of the torso (like a shirt). Sometimes the costume comes with ‘water sleeves’, extra material attached to the sleeves used to enhance or exaggerate the actions of the actor. This is typically worn on stage by performers playing innkeepers and ‘low class’ characters of that ilk.

The tea garment can come in different colours, such as beige or dark brown, but it’s commonly blue which for opera goers makes it instantly recognisable as denoting the lowly status of the tea seller or innkeeper. The tea garment displayed at the AMC exhibition was taken from a story in the epic Water Margin series (this narrates the heroic exploits of 108 legendary outlaws gathered at Liang Mountain. ‘Lin Chong’, head of the Imperial Army, having been betrayed by his friend, is sent into exile to guard an army storehouse. He buys wine from the tea garment-wearing merchant to keep himself warm in a snowstorm just before the storehouse is set on fire in an attempt to have him killed.

Characters wearing the tea garment are typically ugly. It’s a role called ‘chou jue‘ (丑角). A little blob of white paint may cover their eyes and nose, symbolising ‘quick wit’ or else ‘good or wicked’ depending on its exact shape. The tea garment is one of the few costumes that have successfully graduated from the theatrical stage on to television. They really seem to be an accurate representation of what tea house owners – my somewhat downtrodden predecessors in ancient China! – actually wore in their daily work life. Thanks to the Asian Music Circuit and the London Jing Kun Opera Association for bringing this so vividly to life!

Warmly,

Pei

Teanamu Chaya Teahouse

~~ Serene and fragrant TEA entices with promise of rapture in STORE ~~